Over the last year I read a dozen excellent books on Cybersecurity, and I want to recommend some of them – these are books accessible to the general audience and which read like good thrillers, and thus will make time go by faster sitting in airplanes and other modes of transportation. It could be said that all these books focus on malware and that to some degree sensationalize cybersecurity, but that is part of their charm, and that is what makes them ‘page turners’. However, it is important to remember that there is nothing magical about cyberattacks, and it is not surprising that state actors want to wield the Internet, specifically the Internet of Things (IoT) as a weapon. IT systems are complex, and we do not yet have proven methods to write reliable (i.e., correct) software, and hence our vast IT infrastructure is of course vulnerable to attack, and all is fair in love and war. All books however, stress the need to be prepared, and the need to emphasize defense as well as attack capabilities. All the books have significant overlaps (e.g., they all mention Stuxnet).

My first recommendation is Andy Greenberg’s Sandworm, a book that came out in 2019, which details all that is known about the hacker group known as Sandworm, a group that is responsible for major attacks such as NotPetya. Andy Greenberg is such a good writer, and presents the geopolitical context in such vivid detail, that I found myself having a mental conversation with him during the reading of the book. This book is not intended for the Computer Scientist who is interested in the technical details of the attacks, but those details can always be found on the Internet. The description of the political situation in Ukraine is a little simplistic, and I do not agree with the sobriquet of Poland as imperialist toward Ukraine (much of western Ukraine was simply Polish before World War II, such as the city of Lwów), but the history of that part of the world is complex, and this is not the book to unwind it. I have always been an avid reader of the late Harold Bloom, and one of his lessons to writers has been to be sympathetic even to the villain in your story; I feel that Russia’s concerns in eastern Ukraine (Crimea) could have been presented as part of the story.

David E. Sanger’s The Perfect Weapon, published in 2018, is a comprehensive overview of how world’s powers are deploying digital sabotage. Sanger is the national security correspondent for the New York Times and also teaches national security policy at the Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. This book is a study of how cyberweapons are transforming geopolitics, and that they are a game changer of the same caliber as the atomic bomb was at the time of its invention. Sanger was the author of the New York Times article in May 2012 that first attributed the Stuxnet malware (known as the Olympic Games operation to the US intelligence community), to the Obama administration’s secret order to deploy increasingly sophisticated attacks on the computer systems that run Iran’s main nuclear enrichment facilities at Natanz. A well researched, well written book, with a gripping narrative, a great place to start understanding – and demystifying – Cyberweapons.

Bruce Schneier’s Click Here to Kill Everybody, with the subtitle Security and Survival in a Hyper-connected World, is a fantastic read on Cybersecurity in the context of the Internet of Things (IoT). Bruce Schneier is of course very well know in the Cybersecurity community (www.schneier.com) and he is the author of one of the first modern books on Cryptography (Applied Cryptography, first edition 1996). I liked many things about this book, but especially the author’s insights on the philosophy of Cybersecurity. For example:

- Large Attack Surface problem, where the defender has to secure the entire attack surface from every possible attack all the time, but the attacker only has to get lucky once. During my PhD, and for many years after, I worked in the field of proof complexity, where the goal is to study the power of logical theories; this reminds me of a profound observation in mathematics, that universal statements (∀-statements) are often much more difficult to prove than existential statements (∃-statements). A ∀-statement frequently requires the full power of induction, while ∃-statements can be frequently proven with a simple construction (this is a very high-level intuition driven statement).

- Complex systems are very versatile, flexible and so they have lots of options. A classic safe is easy to see if it is opened or closed; yank the handle. But checking whether the permissions in your OS are set correctly is difficult.

- Attribution: it is very difficult to do digital forensics; who penetrated your system? We may all “know” where the attack originated, but the evidence is usually scant.

- And other concepts such as Skills vs Abilities, Small Gains, Skills Gap and Public Education, which the interested reader can find in the book.

Kim Zetter’s Countdown to Zero Day – and older book (2014) based on an even earlier article by the same author in Wired magazine (2011) – describes in great detail the geopolitics, but also to some extent the mechanics, of the Stuxnet malware (mentioned in some of the books listed above). Stuxnet was a sophisticated worm, developed by the US and Isreaeli governments around 2005 (code name Olympic Games), aimed at the uranium enrichment facility in Natanz (Iran), and discovered by the Infosec community around 2010. The worm attacked PLCs Programmable Logic Controllers (PLC) manufactured by the German company Siemens and deployed at the Natanz facility to run centrifuges. There are many interesting aspects to Stuxnet; for example, the first major deployment of a cyberweapon, the attack on the IoT, etc. The book is very detailed, and while this can help experts piece together a very detailed picture of what happened, it could be a little bit dry at times to the casual reader. I would suggest to read this book not being afraid to skip certain parts, especially those that might sound repetitive, or parts with which the reader is familiar already. Still, this book is in my opinion the definitive companion to the Stuxnet malware. For those interested to go even deeper, please keep in mind that there are public repositories containing the Stuxnet code: https://github.com/micrictor/stuxnet

Richard A. Clarke’s Cyberwar is the oldest (2010) and least technical book on this list, but very important as it presents Cyberwar from a policy / national security perspective. Clarke has served in several administrations, starting with president Reagan, and has thought deeply about the national security perspective of all things Cyber. It should be noted that this book has been written with Robert K. Knake as co-author. Often, in the field of Cybersecurity, experts are siloed, and those with command of the technical aspects of the field, have little understanding of, say, legal / policy aspects. This book, while interesting in itself, also has the advantage of defining various concepts in a precise manner that can lead to meaningful policy discussions.

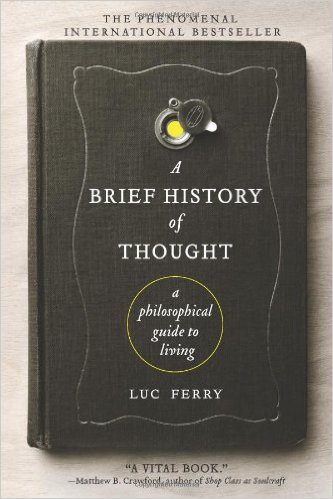

Fantastic history of philosophy by Luc Ferry

Fantastic history of philosophy by Luc Ferry